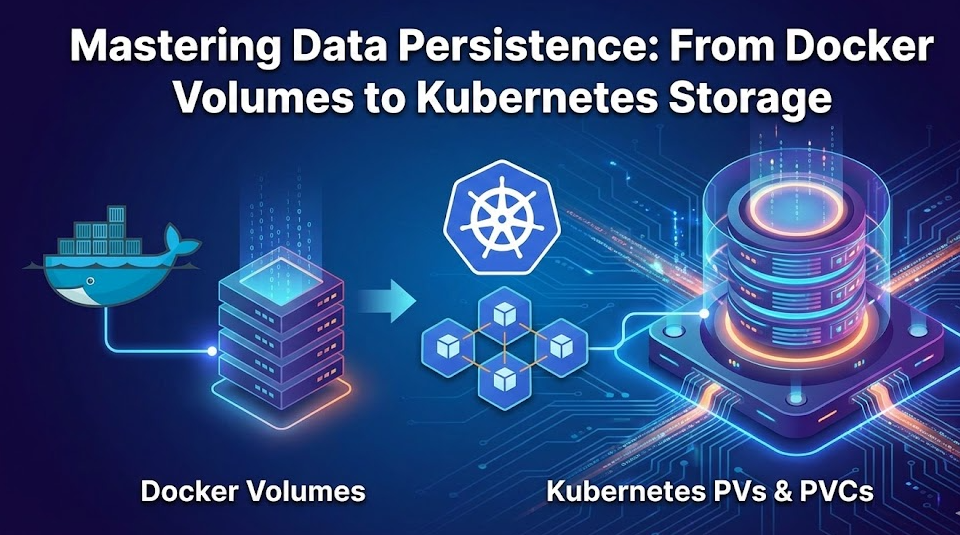

Mastering Data Persistence: From Docker Volumes to Kubernetes Storage

Rishav Sinha

Published on · 4 min read

Mastering Data Persistence: From Docker Volumes to Kubernetes Storage

In the world of containerization, one of the first hurdles developers face is the ephemeral nature of containers. By default, containers are designed to be short-lived. They spin up, do a job, and spin down. While this is great for stateless applications, it poses a significant challenge for databases and stateful applications: when a container dies, its data dies with it. To run databases like MongoDB or PostgreSQL in containers, we need a way to decouple the data from the container's lifecycle. We need the data to persist even if the container crashes, updates, or is deleted. Here is a deep dive into how we handle storage and persistence, starting with simple Docker volumes and moving to the robust architecture of Kubernetes.

The Problem: Ephemeral Storage

Imagine running a MongoDB container for a To-Do application. You add ten items to your list, and everything works perfectly. But if you restart that container or delete it to update the image, those ten items disappear instantly. This happens because the container's file system is temporary. To fix this, we need Volumes. Volumes act as a bridge, allowing data to be stored on the host machine (your computer or server) rather than inside the disposable container.

Part 1: Persistence in Docker

Docker offers a straightforward way to handle this using Bind Mounts. This technique maps a specific folder on your local machine to a folder inside the container. When you run a container, you simply add the -v flag:

docker run -d \ -p 27017:27017 \ -v /my/local/folder:/data/db \ mongo:latest

How it works:

/my/local/folder: This is a directory on your physical machine./data/db: This is where MongoDB saves data inside the container.- The Result: MongoDB writes data to

/data/db, but Docker transparently saves it to/my/local/folder.

If you delete the container, the data remains safe in your local folder. When you launch a new container pointing to that same folder, it picks up right where you left off.

Part 2: Persistence in Kubernetes

While Docker's approach works great for single machines, Kubernetes (K8s) operates on clusters of multiple nodes. We need a more scalable, declarative approach to manage storage across a fleet of servers.

Kubernetes introduces a hierarchy of resources to abstract and manage storage: Storage Classes, Persistent Volumes (PV), and Persistent Volume Claims (PVC).

1. Storage Class (The "Type" of Storage)

The Storage Class acts as a blueprint. It defines the "kind" of storage available in your cluster—whether it's high-speed SSDs, cost-effective HDDs, or cloud-specific storage like AWS EBS. It allows administrators to define different tiers of storage service.

2. Persistent Volume (PV) (The "Actual" Storage)

A Persistent Volume is the actual piece of storage in the cluster. It’s a cluster-wide resource, similar to a node. It details the capacity (e.g., 10Gi), access modes, and the physical path to the storage (or the cloud ID).

Crucially, a PV has a lifecycle independent of any individual Pod. If a Pod is deleted, the PV (and your data) hangs around.

3. Persistent Volume Claim (PVC) (The "Request")

This is where the application comes in. A Persistent Volume Claim is a request for storage by a user or a Pod.

Think of it like a ticket system:

- PV is the available supply of hard drives.

- PVC is a request saying, "I need 1GB of storage with Read/Write access."

Kubernetes automatically matches the PVC request to an available PV. The Pod then uses the PVC to access the data, never needing to know the complex details of the underlying infrastructure.

The Declarative Workflow

In a Kubernetes manifest, the flow looks like this:

- Create a PV: Define 1GB of storage mapping to a host path or cloud volume.

- Create a PVC: Request 1GB of storage.

- Deploy the Pod: In your Deployment YAML, you reference the PVC.

When the Pod starts, it asks the PVC for storage. The PVC binds to the PV, and the data is mounted into the container. Even if the Pod moves to a different node (depending on your storage backend) or is restarted, the PVC ensures it re-connects to the correct data.

Conclusion

Handling state in a stateless world is a fundamental skill for modern DevOps. Docker provides the quick, imperative tools to get started locally, while Kubernetes offers a robust, abstract system to manage storage at scale. By mastering PVs and PVCs, you ensure your databases are as resilient as your application code.

If you find this concept of PV, PVC, and Storage Classes a bit confusing, I have made a detailed video walkthrough where I demonstrate this entire setup with a real React & MongoDB application. You can check it out here: Watch the detailed tutorial